Introduction

Chinatown’s pavements are special. How special, you ask? They have Chinese proverbs imprinted on them. Three different ones can be found all around the area. Because a new year has just started, Chinatown started a small project of its own. A series about these proverbs. For three weeks, starting today, we’ll publish a story about one of the proverbs right here, on our website.

Proverb stories: part 1

前人栽樹,後人乘涼

Translation: One generation plants a tree, the next enjoys its shade.

Broken down into pieces

前:before, former, earlier

人:human, people

- 前人:former generations

栽:to plant (trees, plants, etc.)

樹:tree

後:after, later

人:human, people

- 後人:later generations

乘:take advantage of, enjoy merits of

涼:shade, chilliness, coolness

- 乘涼:to enjoy the shade

The idea

This proverb tells us that a generation of people always works hard for their children to have a better life. Rather applicable to Chinatown, we must say. After the second world war, many Chinese flocked to the area and started businesses. More often than not, these people worked intense restaurant jobs, all their life. They did this, so that their children could go to school, be educated, and have a better life than the parents.

These proverbs often seem difficult to understand if you don’t speak Chinese, and even if you speak a little, they are rather daunting. We must agree with that. Next week’s proverb isn’t as straight-forward as this one. Why is that, though? Mostly, it is the case that the root idea of these proverbs is found in Daoism or Confucianism. Given that these philosophies are not as widespread around the West (at least not among Dutch people or others, from West-Europe or the Americas), it may be difficult to follow the proverbs’ logic.

However, we must say that each Chinese proverb has something charming about it. There are thousands of them, some of them very simple, others nearly impossible to decipher. Though, there is more mystery about them. Perhaps the key to this mystery is found in the fact that Chinese is a rhythmic language. Phrases, especially proverbs, are often found to be symmetrical, meaning that they consist of an equal amount of characters both before and after the comma. Often, as also seen in this week’s proverb, these are clusters of four characters. Though, sometimes there are other numbers. Five and three are also seen. Though symmetry is often kept.

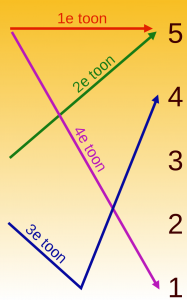

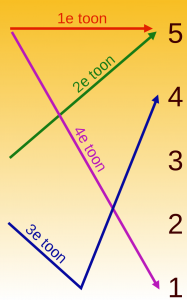

Rhythm isn’t only found in equal amounts of characters. Because Chinese is a tonal language, these tones also add rhythm to phrases. Here’s a quick overview of the tones found in Mandarin Chinese:

Perhaps you won’t immediately believe us, but you can find tones in English too! Not as many as Chinese, and they are used differently, but still. Check it out:

“What!?”

“That!”

When asking a question, your voice rises a little at the end of the sentence. That’s comparable to the 2nd tone in Chinese. When you answer a question or emphasize a word in a sentence to make your message clearer, you’ll pronounce the word a bit louder. That is almost the same as the 4th tone. Check out this sentence:

“What are you going to do?”

Especially when asking something in a rather surprised way, you’ll use the 2nd and 4th tone frequently. Here, the word ‘what’, because of emphasis, is pronounced in the 4th tone. The word ‘do’, being the final word of the sentence, will be pronounced in a higher pitch, as it indicates a question. There you have it, 2nd tone.

In Chinese, each word has its own tone. Here you can see how to pronounce this week’s proverb. You can see that the little signs right above the vowels indicate the tones also seen in the picture above.

Qián rén zāi shù, hòu rén chéng liáng.

Tones in Chinese are extremely important because they do not emphasize meaning. Instead, you can change the meaning of a word with it. Check out the most famous example of this:

媽:mā:mother, mom

麻:má:hemp

馬:mǎ:horse

罵:mà:to scold

嗎:ma:makes a sentence into a question sentence

Pay close attention to the tone you use, next time you tell this story to someone!

See you next week, when we’ll be talking about 道可道,非常道。

拜拜!Bye-bye!